In theory, absolute return bond funds are well suited to the secular end of the 30-year fixed income bull-run. A plethora of funds have been launched and adopted promising positive performance regardless of market conditions.

“Shorting is expensive if you get it wrong. Even if a manager is not restricted from doing so, it is a question of whether they have the courage of their convictions. People say they will, but we would have to see the world end before they actually do.”

Pater Martin

In an environment where the future direction of interest rates is uncertain with risk skewed to the upside, and credit spreads approaching or at fair value, absolute return fixed income strategies appear a natural solution. They should provide diversification and dampen interest rate exposure. Theory and practice often differ markedly, however, and delivering genuine fixed income absolute return is easier said than done.

Peter Martin, head of fund manager research at JLT Benefits Solutions, is keen on the idea of absolute return bond (ARB) funds and has been suggesting the strategy to clients for some time, but has discarded most of the products on the market. “You’ve got to be very careful where you put your money,” he warns. “There are some good products out there, but it is a small sub-set of what is available. Too many long-only managers have brought products to a space that is fashionable where, in truth, they lack the correct skill and mind-set.”

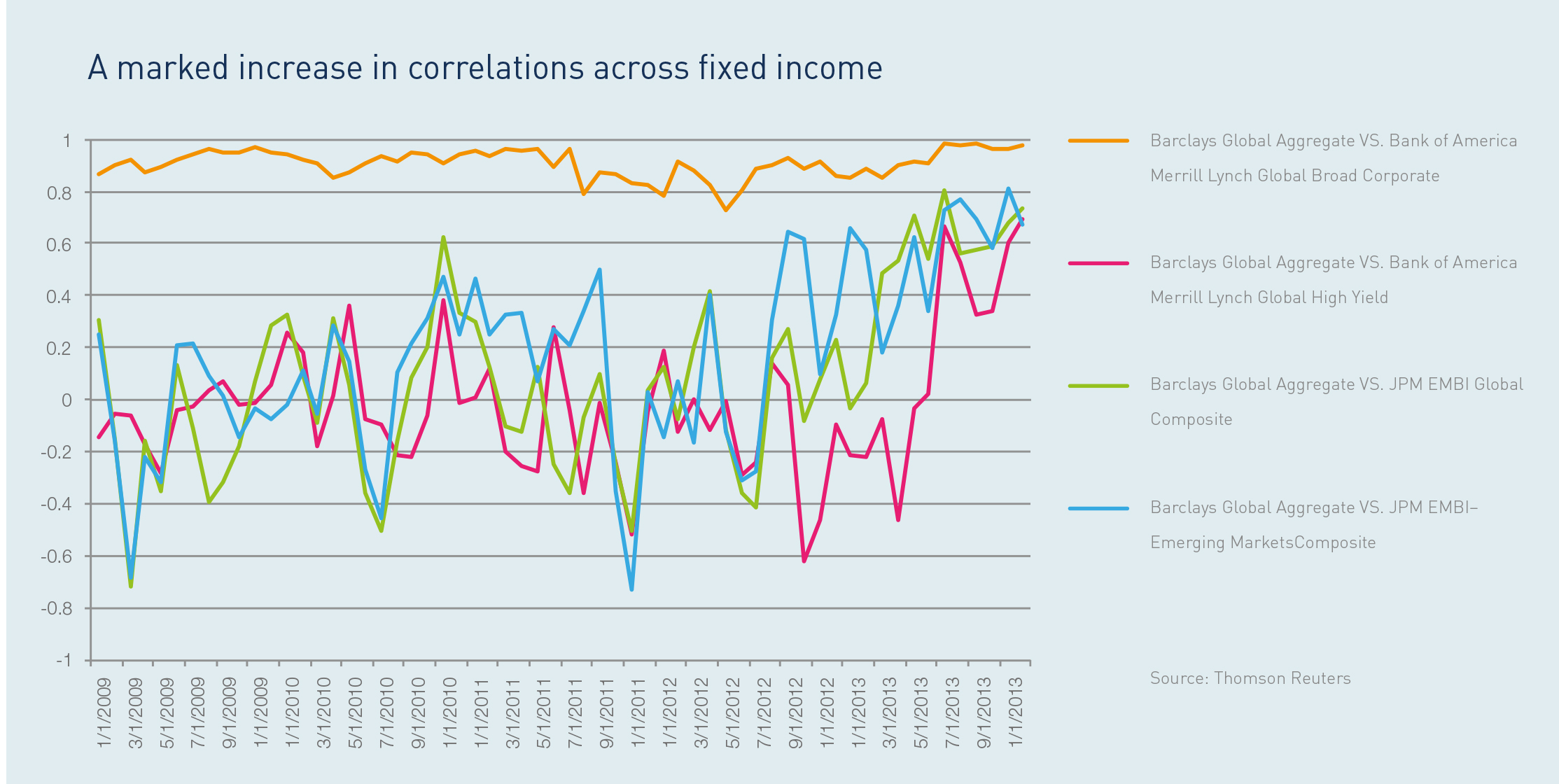

The inherent difficulty for long-only managers is that diversification alone will not deliver. This was proven last year by the widespread correction across government bonds, investment grade and high yield credit as well as emerging market debt caused by the Federal Reserve’s taper talk. May, June and August saw sharp declines across a broad range of benchmark indexes including the Citigroup World Government Bond index, BAML’s Global Broad Corporate and Global High Yield indexes, Barclays Global Aggregate, and JPM’s EMBI Global Composite and GBI-Emerging Markets Composite. Correlations between the Barclays Global Aggregate and these other indexes have also increased markedly over the last five years, particularly since mid-2012 (see chart).

Falling short of the mark

In a market correction, the ability to protect capital and product outperformance is heavily dependent on a manager’s ability and willingness to short. “Shorting is expensive if you get it wrong,” Martin says. “Even if a manager is not restricted from doing so, it is a question of whether they have the courage of their convictions. Lots of people say they will, but we would have to see the world end before they actually do.”

Shorting fixed income is considerably more complex than equities, not least because of the range of structures, maturities, currency and seniority on bonds for each issuing government or company. Considerable skill and resource is required to carry out the necessary detailed analysis by both analysts and portfolio managers. Fixed income securities also inherently have two components: duration and the counterparty risk premium. Removing duration requires a zero or negative exposure to interest rates. Being underweight (often commonly termed as being ‘short’) is not enough.

According to Roubesh Adaya, senior associate at investment consultancy, bfinance: “The ability to achieve zero or negative duration is something that very few managers can do.” Being truly short duration can be punishing as it means paying away the positive carry and accepting a negative run-rate. This is especially prevalent in today’s environment of relatively steep yield curves as future interest rate rises are priced into the market. As the old saying goes: “being right too early is just as unprofitable as being wrong.” “Timing when to go short is a key factor for generating positive performance,” says Richard Ford, head of European fixed income at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. “Managers need to be very active as the market is already pricing in increasing rates. We are clearly on a path to higher rates, but the ability to judge the pace of that transition will be critical.”

Managing duration alone will unlikely deliver positive performance irrespective of market conditions. Bfinance research shows duration to be a poor contributor to performance. “

No managers are able to consistently deliver by focusing solely on the duration component of a portfolio,” Adaya says. Being short credits is, arguably, even more difficult because of the associated costs, liquidity issues and spread. “Implementing a physical bond short exposure in credit means having the ‘carry’ from upward sloping yield curves and credit spreads work against you,” explains Chris Redmond, senior investment consultant at Towers Watson. “If a manager is paying away 2% to 5% per annum running yield to maintain a short exposure, if held for two years the profit from the deterioration in credit quality would effectively need to be up to 10% before the position becomes profitable. Consequently, being able to predict the timing of the credit spread sell-off is important.”

Making money shorting credit also requires the ability to structure a trade efficiently so the costs are minimised and liquidity is not compromised. The market for borrowing fixed income securities is relatively under-developed versus equities and is therefore more opaque and expensive. While equity borrowing typically attracts a fee of between 20 to 40 basis points (bps), bonds typically cost around 50bps, but can range from 30bps to 150bps. “The bond lending market is like the equity market five years ago,” says Stevan Bajic, portfolio manager at Altana Wealth. “Generally there is less data on bonds available for borrowing so it is difficult to gauge availability and managers have to rely on their brokers for their perspective on this point. Less transparency tends to mean higher borrowing costs. Special names are particularly hard. Crowded names become harder to borrow as a company is placed under more stress.”

Implementing short trades cost effectively and quickly requires managers to embrace a wider set of instruments than just cash bonds, but importantly, not to the extent liquidity is impacted. Liquidity is already tighter than pre-2008, amplifying market moves.

As Faraz Sultan, head of portfolio management and advisory at HSBC Alternative Investments states: “Liquidity is paramount. Illiquidity would defeat the purpose of absolute return bond funds by making it difficult for them to navigate volatile periods. We look for managers who can add value during periods like Q2. “We had a stress test earlier this year and the short exposures and hedges our managers held helped us outperform our benchmark in May,” Sultan continues. “Most went into that period with a reasonable short book.”

- 1

- 2

- »

Comments