The impact of the oil power struggle will be meaningful and far-reaching for institutional investors.

As global oil supply has grown and become more diversified, the balance of power has shifted. Today’s low oil prices are a direct result of structural changes in the industry and a fight to regain control of price setting.

As balance returns to the market, the oil price will recover, although the length and shape of that recovery, and the turbulence it throws up, are still highly uncertain. However, the impact of the oil power struggle on long-term investors’ portfolios will be meaningful and far-reaching.

SHIFTING SANDS OF COMPETITION

The 70% fall in global oil prices over the last 18 months has predominantly been due to a changing competitive environment as major producers ramped up production in the expectation prices would recover quickly following the 2008 recession, and the ‘shale revolution’ in the US gathered speed.

Global oil supply subsequently became much more diversified and changed the balance of power to determine oil prices globally. OPEC has traditionally been the world’s marginal producer and therefore had significant price-setting power. They could simply increase or decrease production in order to sustain a desired price. The emergence of shale oil as a disruptive technology has moved the marginal barrel in terms of non-OPEC production from slow moving, high-cost projects to more nimble, lower investment/cost output. As such, a decrease in production by OPEC, instead of pushing up prices, is now simply replaced by competitors.

Tom Brooke-Smith, senior investment consultant at Willis Towers Watson, says: “Recent price falls have been more to do with supply side changes than demand. Oil markets have moved to a more ‘competitive’ structure with the emergence of shale oil undercutting much of the previous cost-curve.”

As well as driving down cost and changing the price impact of the marginal barrel, the more geographically and politically diverse range of supplies has effectively reduced the political risk factored into the oil price. Daniel Lacalle, author of The Energy World is Flat: Opportunities from the End of Peak Oil (Wiley), says this has “removed the geopolitical premium in the oil price that was due to the reliance of OPEC and unstable countries” for supply.

Today, experts estimate global oversupply to be in the region of 1.5 million to 2.5 million barrels per day. According to Fiona Boal, director of commodity research at Fulcrum Asset Management: “Commodity markets are not difficult to understand: when you have more than you need, prices go down and that’s exactly what has happened in the oil market. The supply glut started with the impressive growth in US shale oil production, but has been exaggerated by a change in strategy by OPEC, who shifted at the end of 2014 to maintaining market share irrespective of price.”

SUPPLY AND DEMAND

With OPEC still able to cope with the decreased profitability associated with lower oil prices far better than many higher-cost producers and its strong desire to regain market share, a significant rise in oil prices could yet be some time off.

Solomon Nevins, senior investment manager at Architas, warns: “Until OPEC has achieved its goal of reducing non-OPEC supply through an environment of lower prices, it would be self-defeating to flinch and cut supply, so we expect the price of oil to remain in the narrow $27 to $35 range for some time. OPEC will want to see a pick-up in US shale defaults, a credit crunch in the sector and a meaningful fall in non-OPEC supply before they are comfortable reducing production.”

Furthermore, Iran, whose oil production fell sharply under sanctions, is aiming to get its oil output back up to pre-sanctions levels within the next year. Even if it doesn’t manage to get back to those levels in that timeframe, Iran offers some of the best quality oil and lowest-quality production globally and, as such, the availability of more Iranian oil could serve to slow down the balancing of supply and demand dynamics in the market.

IMPLICATIONS FOR LONG-TERM INVESTORS

The implications of the fight for market share are far-reaching for long-term investors. Oil extractors are clearly suffering the pain, with 14,000 job cuts announced by BP and Royal Dutch Shell, whose share prices are down over 25% and 27% respectively for the year to 24 February.

According to Stephen Jones, CIO of Kames Capital, long-term investors also face the threat of falling dividends. “People are questioning the dividend-paying abilities of big oil companies at these prices, particularly Shell and BP,” he says, adding that a fall in dividends could be potentially painful for long-term investors given the prevalence of these companies in index-racking investments. “Some companies are diversified and strong enough to cope for a while, but they won’t be increasing their dividends for a while even if they can maintain them,” Jones says.

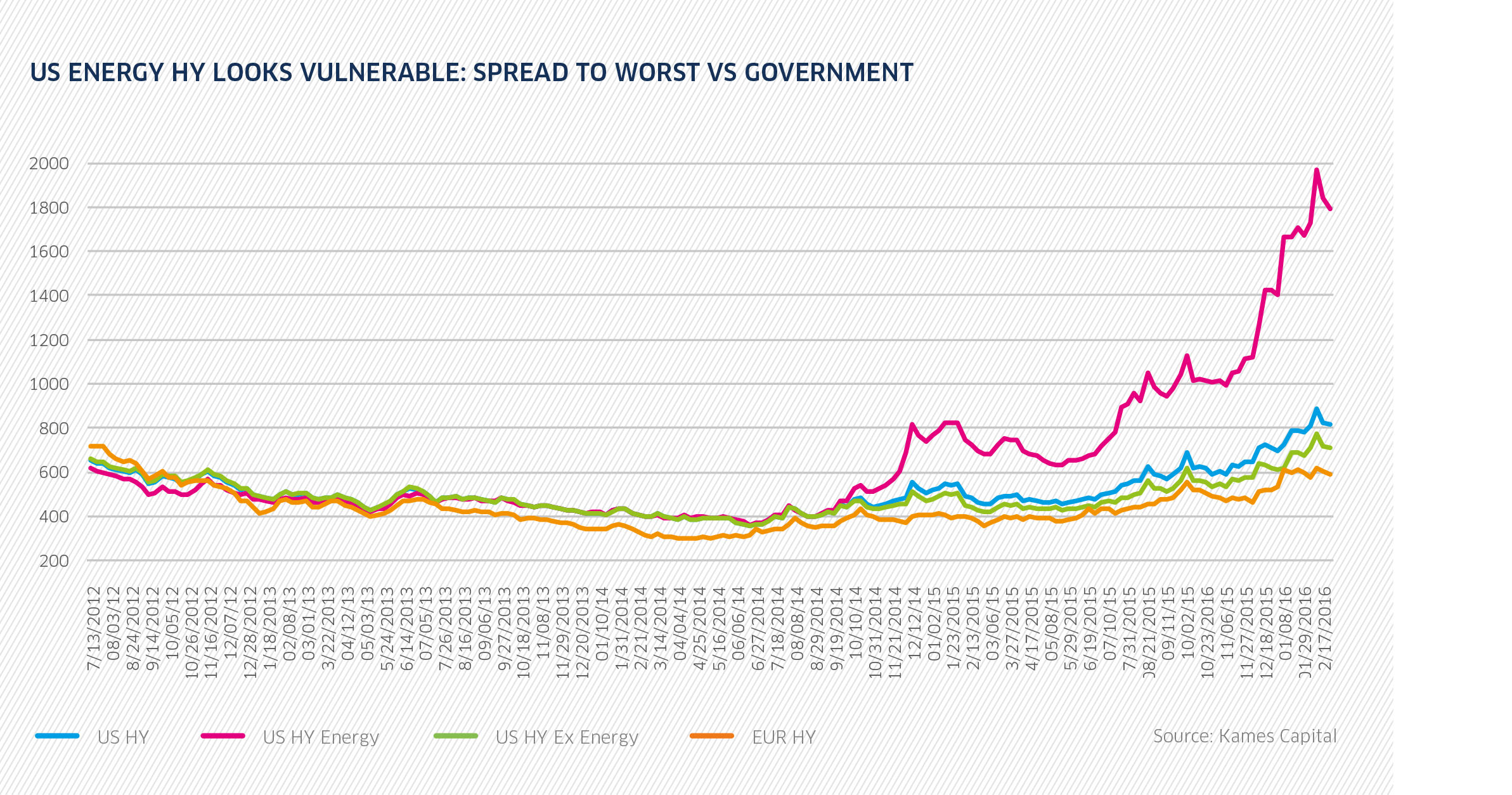

Furthermore, with OPEC targeting the US shale market, there is growing concern about the US high yield market, a financing route that has proven popular with shale producers. Jones estimates around 18-20% of the US high yield market is exposed to shale and “looks very troubled”. “Prices have moved to reflect very serious defaults and hair cuts,” he says.

As chart 1 shows, spreads on US energy-related high yield debt have soared from 359 basis points on 20 June 2014 to a peak of 1971 in early February. The wider US high yield market has suffered some contagion, with spreads more than doubling to just under 900 basis points over the same period. Perhaps the most acute impact on institutions, particularly those with liabilities, is the continued deflationary pressure weighs on discount rates.

The pound fell strongly in late February as the Bank of England (BoE) changed its rhetoric around the future of interest rates as inflation continually fails to reach the BoE’s 2% target. According to Peter O’Flanagan, head of trading at Clear Treasury: “GBP/USD dropped below the key psychological level of 1.4 and is pressing fresh lows.” At the very least, the falling oil price will delay the timing of future interest rate hikes in the UK and US. “Nominal yields have been very well bid,” says Kames’s Jones. “Yield curves are flattening. The ever-reducing discount rate against liabilities puts increased pressure on institutions.

Willis Towers Waton’s Brooke-Smith points to a significant set of second order effects that are less well understood. “One of the key pillars supporting US economic growth in recent years has been the growing investment in the shale oil industry,” he says. “On a forward looking basis this impulse is likely to move into reverse, with impacts on employment and therefore consumer spending. During 2015 the investment impact likely offset the wealth effect to aggregate consumers, who appear to have saved much of their improved disposable income. “The combination of these two impacts in 2016 could well be negative,” he adds. “If the US tips into recession this will have wide ranging impacts on institutional investor portfolios.”